Over the last decade or so, the growth of social media and influencer culture has given rise to a uniquely modern term - “parasocial”. Parasocial relationships are defined as uniquely one-sided connection with someone that has no ability to reciprocate. The term existed in scientific circles in the 1980s, but really came into fashion with the advent of the pandemic in 2020, during which many people sought necessary social interaction through celebrity or media connections. Studies were conducted that showed individuals who lacked friends in real life made up for this deficit through intensely formed parasocial relationships, often with influencers on TikTok or YouTube. Of course, this type of connection has been observed in most of human history - medieval royalty, religious leaders, and even “celebrity” criminals like Charles Manson or Ted Bundy had incredibly devout followings of rabid fans, but something about the 24/7 aspect of digital celebrities has made these relationships feel far more normalized in 2025.

There are plenty of films that circle this subject of parasociality, many of them foreseeing a future of desired obsession before the rise of the term itself. Martin Scorsese’s King of Comedy, Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue, and in a more documentarian sense, Gregory Nava’s Selena all brilliantly show the dark side of one-sided worship. For me, however, there is no more prescient example than Shunji Iwai’s All About Lily Chou-Chou. This is a film, as you might guess, about Lily Chou-Chou: a fictional musician that first appeared as part of an online novel published by Iwai in 2000. The project was fictional only in appearance, as real music began to slowly trickle out ahead of the 2001 release of the film itself. Lily’s music is psychedelic and noisy, but grounded entirely in turn of the century Japanese rock roots. Along with the music, Iwai created an abundant backstory for her, being heavily tied to the sounds of the past and the future.

The film utilizes a mix of this music and the timeless songs of French classical composer Claude Debussy, two artists that could not be further apart in time and place, and yet seem to come to a common sort of calm in the storm of their realities. Throughout this piece, tracks utilized in the film are placed at the start of each section to accompany your reading, as the backing music of the film is just as important as the narrative on screen. The film’s story is complicated and confusing, but never quite leaves the ground, held tightly by the safe haven of Lily and Debussy’s music. This is a challenging film to watch and analyze, but its singular existence is one of immense importance that deserves discussion.

Salvation in Sound

All About Lily Chou-Chou takes us through a single year in the life of two Japanese teenagers, Yūichi Hasumi (Hayato Ichihara) and Shūsuke Hoshino (Shugo Oshinari). The story dances in a circuitous loop around the events of the year, never quite feeding us information in a linear fashion. Clues and consequences are provided non-sequentially, leading to a viewing experience that is far more experiential than it is focused. So often, I have a personal shortcoming with films like this, stories that tackle dreamy, ethereal stories in ways through forceful bending of the mind. This film, however, just feels different - this structure, which often leads only to confusion for the sake of technicality, lends itself perfectly to this story of adolescence. Think back to your own childhood, the memories might be there, but I doubt they are in order. This formative year that we watch for Yūichi and Hoshino feels congruous, it feels sensical, but it is plated in a way that highlights a confounding paradox of isolation and causality.

The film begins in the mid-point of the year, just as the second term of junior high school begins for our protagonists. Yūichi moderates a message board fansite for his favorite musician, Lily Chou-Chou, whose music you are listening to right now. He was introduced to Lily by his friend at school, Hoshino, and the two form an immensely strong bond over her music. Yūichi goes by the username “Philia”, an ancient Greek word for love, especially that of an abnormal kind. He talks with other users on the site regularly, perhaps none more than a particularly active user named “Blue Cat”. We will come back to the significance of this name in due time, but there are a number of fairly open interpretations - it will become clearer throughout this piece, but this film is laced with an enormous amount of cryptic lore and metaphor, much of it intentional. This way of filmmaking, Iwai’s obsession-forming universality, is something that helped inspire this film itself. The musician that Yūichi’s fanpage is centered around is the digital manifestation of the film she exists within, creating this enveloping experience of a meta-textual labyrinth that leaves you in a wash of information with no answers. Every detail of the film could mean something, and to those dedicated to digging through All About Lily Chou-Chou, the meaning becomes infinite.

This relationship between artist and fan, between creator and observer, is the primary dynamic at play in this film in these interstitial moments. While the narrative bounces between sporadic moments of Yūichi’s year, bizarre, jarring moments of pause appear routinely in the film, showing us the forum conversations between Philia and Blue Cat. The monotony of the clicking, the unwavering palette of white text on a black background, it all makes for this strangely profound environment that these digital characters exist within. We see the vibrant, vérité world that the “real” characters live and play in, and yet the truest emotions spill out over the simplest of backgrounds. For Yūichi, this is safety. Lily is safety, being Philia is safety, being in this world that he has found meaning in, that is the only thing he really wants. In this strange way, submitting to Lily, allowing himself to be all in on her music and persona, gives him control. He has delved deeper than nearly anyone else into this niche, microscopic world of lore, and that knowledge is an ever-burning fuel. This film, and all films for that matter, do the same exact thing, and Iwai knows that. The horrors that live in this film, the incredibly confusing crypticism, they are there to elicit some degree of wonder or shock to many, but this film is so much more to the lucky few that let themselves be consumed by it.

Ethereality

All About Lily Chou-Chou came at a rather pivotal point for the youth of Japan, with its turn-of-the-century release capping a period of immense cultural shift for teenagers and young adults in the rapidly modernizing nation. In a notable 1999 article from the New York Times, Howard W. French outlined the concerns (at least, those observed from the west) somewhat bluntly:

“Still, for Japan, whose conservative, nearly mono-ethnic society sometimes conveys the feel of an immense village where elaborate social codes are universally recognized and respected by nearly all, the spread of criminal behavior among young people represents a dramatic departure from the norm. And if the phenomenon goes unchecked, many Japanese fear, it will destroy one of the features that contributes most to Japan's sense of uniqueness: unquestioned security.”

- Howard W. French, New York Times

Arrests of minors for “violent crimes” more than doubled between 1990 and 1998, and almost did the same in the three years between 1998 and the 2001 release of this film. French’s story cites some of the more notable cases that rocked the country - the killing of 16-year-old Hanae Nagatani by a young male that had been stalking her for months and the strangling of a 23-year-old housewife and her 11-month-old baby by a high school male in Yamaguchi. French, a 42-year-old American citizen at the time of the piece’s publishing, did enough to outline his facts with an argument, but the result comes off as the written equivalent of a concerned shrug. He cites absent parents, strict schooling, intense youth schedules, and an overarching, nation-wide social shift that creates the conditions for neglect and eventual outburst. I am not necessarily arguing he is wrong on a sociological level, but how were the children of Japan supposed to take this answer to their concerns? These teenagers were both angry and scared, their friends were being kidnapped, sexually assaulted, and killed, and the answer was that it is a problem nation-wide? For so, so many, this answer meant absolutely nothing, and the only solution was further retreat. Retreat into the safety of isolation, the peace of the ever-growing digital third spaces that at least create a facade of safe sociality, and the continued, buried rage over conditions far from their control.

This film, often times explicitly, shows the realities of this world. We see Yūichi beaten by Hoshino’s gang, and forced to masturbate in front of them. We see multiple instances of Hoshino blackmailing young women from his class into enjo kōsai, a sort of relationship where older men will pay money for sexual access to vulnerable, high school age women. Yūichi develops a crush on his classmate Yōko Kuno (Ayumi Ito), a soft-spoken girl who clearly is afraid to excel despite her natural talents in class. Yōko offends the school’s girl gang (another growing problem in Japan at the time), leading to Hoshino trapping her in a warehouse while his lackeys rape and assault her. These events are horrific, they are traumatic, but I think the easy response is to be only disgusted and ashamed. Iwai, moral or not, wants us to be intrigued, wants us to be confused, angry, upset, all of these things at the same time, because that is the reality. We don’t have to understand evil, we don’t have to accept some individual personality flaw or some sort of societal shift as a predecessor to villainy, we are allowed to simply exist in the horrifying perplexity of reality. While so many films give an escape route for explanation or reasoning, All About Lily Chou-Chou does the opposite - we sit in the filth, in the squalor of the situation that surrounds every second of this film, and just… let it be. Yūichi can’t do anything, even when he tries to help one of the girls trapped in this relationship, she refuses his aid and later dies by suicide. It is awful, undeniably, but that is the point. The film is not about seeing the ending, or even the path that got us here - only about existing in this horribly confusing headspace of these teenagers, and letting that feeling flow deep into every inch of your soul.

Lens of Lucidity

As the film reaches its midpoint, Iwai capitalizes on the pause in the school year to give us the incredibly strange “Okinawa Arc”. This is a trope of many different pieces of Japanese media (and somewhat reflective in reality, to be fair), the idea that every summer consists of a vacation to the nation’s tropical island getaway. Yūichi, Hoshino, and most of their friends get a much-needed breather from their immense efforts at school to enjoy the sunshine, water, and fresh air of Okinawa. At this point in the story, things are still entirely clean between our protagonists - Hoshino has introduced Yūichi to his favorite musician, Lily Chou-Chou, and the boys all work very hard to be the best in all pursuits. Hoshino is the class president and leader of the school’s Kendo Club, things that Yūichi both respects and aspires to mimic. While on the trip, however, things change quite suddenly - following a near-death experience in the unrelenting open ocean, Hoshino barely survives drowning and is revived by the Okinawan locals. It seems, both to us and the film’s characters, that the Hoshino we knew is no longer with us. What remains is someone who has lost the motivation to be the best, to be admirable and liked, and who falls deep into a violent, manipulative role. Upon their return to the mainland, Hoshino becomes the image we are first met with in the film’s first act - a bully, gang leader, and truly evil person.

While in Okinawa, Iwai completely changes the production of the film, shooting the entire sequence essentially on a shaky hand-cam. The whole film is shot digitally, a grainy, hyper-modern choice inspired by Iwai’s close friend and fellow director Hideaki Anno. The entire saga feels unstable, almost dream-like, a contradiction to the style itself which could not be more realistic. Iwai frequently introduces other new ways of seeing the film - much of the nighttime sequences are filmed with this faint green headlamp, almost replicating a sort-of “tactical night vision” look, though far more grimy. At times, we see shadows and artifacts left by the crew themselves, and it remains unclear (likely intentionally) if this was an accident or a detail for dedicated fans to notice. The film’s climactic ending is shot outside of a Lily Chou-Chou concert, a real production that Iwai coordinated with fans of the internet novel that served as the genesis for this film. Extras were given an index card with information about their character, and the immensity and scale of the event feels real. Everything about this production feels juxtaposed in this way, coming off as this ethereal, heady, psychological dream sequence while also feeling more like a documentary than a film. It is a remarkable achievement of filmmaking to say the least, and much of it should be attributed to this confusion that Iwai elicits without straying into absurdity.

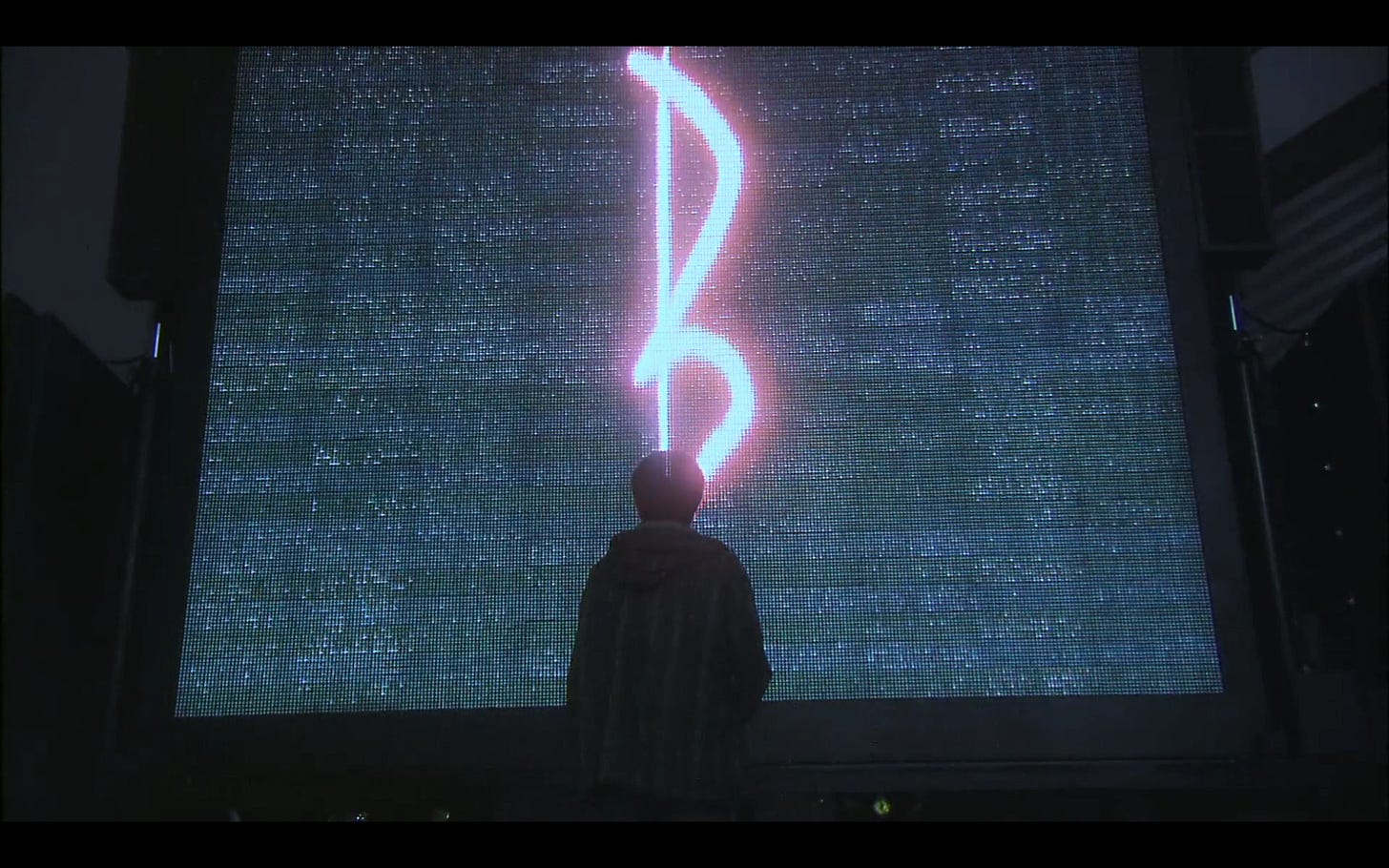

At the aforementioned concert scene, we get the cherry on top of this film’s primary narrative, as Yūichi excitedly attends his first Lily show. He has coordinated with Blue Cat to meet at the concert, who he will recognize by the green apple that his anonymous digital friend will bring. Yūichi searches through the crowd, eventually being interrupted in his search by the worst sight possible: Hoshino. His former friend and later bully that introduced our main character to Lily’s music has been nothing but a persistent evil for the second half of the school year, and Yūichi attempts to avoid conflict entirely. Hoshino sees him, chases him down, and sarcastically embraces the much smaller Yūichi. Perhaps more frightening than the appearance of Hoshino is the green apple in his hand, marked with the phrase “@blue_cat” in permanent pen. Yūichi, as usual, does not say anything - he lets Hoshino take his ticket, then watches as it is ripped into shreds, left to blow away into the crowd. Yūichi is left alone, outside the venue, made to watch the entire concert on the LED screen. The only real connection that Yūichi had left, the online safe space communication between Philia and Blue Cat, has now gone the way of every other relationship in the film. Nothing is safe, there is no respite from the confusion of reality.

“Blue Cat” has a number of possible meanings in Japanese culture, but I have tended to rely on the relation it has to Doraemon, a classic Japanese manga series that first premiered in 1969. The story follows Nobita Nobi, a young boy who is kind and honest, but also unlucky and unfortunate. He tries what he thinks is his hardest, but typically falls into spells of laziness that result in poor grades and a lackluster social life, until he is saved by a time traveling blue robotic cat named Doraemon. The cat has been sent by Nobita’s great-great-grandson in the 22nd century, meant to save Nobita from this life of near-misses. Doraemon helps Nobita fight his bullies using futuristic gadgets, but these efforts usually result in unintended consequences for both the present and future. It is a beloved story with both simple and complex takeaways, but the choice to make Hoshino “Blue Cat” is fascinating - does he see himself as this sort of time traveler? In so many ways, the way he speaks on the Lily forum are kind and profound, completely contradicting the reality of his vicious behavior in school, and I think Iwai wants us to at least question if there is any sort of reflection or regret. I think Hoshino wants to go back, to save his past and make a better life for his future, and this name choice, like Philia’s, is left as just a crumb to ponder over.

Learning to Fly

For as well as this film depicts the confusing non-linearity of adolescent memory, it is even better at showing the other side of the coin, something that critics often call the “finding God” moment of films. The context here is barely religious in a theological sense, but the description is certainly fitting emotionally. The first of these moments comes for Yūichi, when he finds the poster for Lily’s “Erotic” album on the side of the road. This, for Yūichi, is everything. From this moment on, he gives everything he can to being a dedicated member of Lily’s fanbase, finding more meaning in his own life through her music than anything else. We see a similar moment for Shiori Tsuda (Yū Aoi), the young girl coerced into enjo kōsai, just before her death. She sees a group of people in an open field flying kites, and asks if she can try - she has always wanted to fly, after all. For just a moment, Shiori experiences euphoria of the singular kind, a final moment of freedom before her demise. Lily’s Flightless Wings blares over the dizzying scene, and for just a moment, the worry of the world fades away.

For these characters, the world of Lily, the music of Lily, that is their church. Iwai is telling us in no veiled terms that temples are everywhere for those with eyes to see, and these specific, soul-discovering moments are what penetrates the ether of memory. What matters in the timeline of your life? For Yūichi, the answer is Lily. Discovering Lily, finding hidden messaging in her music and the details of her life (did you know she was born on the same die that John Lennon died?), this is his escape. In a world of horrifying reality, Iwai takes us on the path least traveled, showing us that seeing the world in this unresolvable, confusingly maze-like fashion is not just necessary - it is the only way to be. We cannot diagnose or understand, all of that is an effort in futility, but we can feel, deeply and broadly, and attempt to simply exist in this ether.