Typically, I find myself easing into discussions about films with vague, esoteric introductions about the human condition, filled with florid prose meant to elucidate some sort of intrigue (this sentence counts as that). For many pieces, this is appropriate - I intend to make the seemingly obscure become approachable, to highlight my own appreciation of the details that might not be noticed otherwise. If there is a single film that does not need this introductory idyll, it is this one - Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite.

To me, this is a perfect film. Every single line, every single shot, and the way they are all strung together is so precisely crafted with an amount of care that only a master can commit. While this film can be marveled at from so many unique angles, I want to hone in specifically on the screenplay itself. I will outline some of the key moments in the film, how they are written, and what role they each play in making this Bong Joon-ho’s greatest work. Warning - spoilers ahead.

Note: I will refer to the selected scenes with sequential numbers (1, 2, 3, …) - these identifiers do not correspond to the actual scene number listed in the screenplay, rather only the small collection that I have chosen to include here.

Scene 1: Opening Image

It is cliché but it is effective for a reason - a film can hook you with inescapable grip purely from the opening image. The goal of these scenes and shots is to establish the world, establish the present condition of our protagonists or antagonists, and convince you, as a viewer, to stay seated. It can be a delicate balance for filmmakers between exaggerated, hyperbolic set pieces that feel far too fetched to be convincing, and meaningful, artistic images that lay the first layer of color upon a work yet-to-be-finished. In the opening scene of Parasite, Bong Joon-ho walks this tightrope perfectly.

The film begins with a slow, delicate panning shot starting at street level and moving carefully down. We see a grimy apartment, dotted with small rays of daylight piercing through the mud-stained windows. The old ceiling fan affixed to the cracked ceiling is adorned with laundry, drying in the only place it has room to. The street outside is urban enough to be bustling, but hidden enough not to be. We hear yelling and shouting as a young man runs through the room maniacally. We pan through the clearly lived-in apartment to the bathroom - the camera is centered on an elevated toilet surrounded completely by half-used bottles of shampoo and old towels. Here, for the first time, we see our protagonists. The two young characters, assumed to be siblings, are both hoisting their phones high to the ceiling, desperately trying to get a Wi-Fi signal in the dimly-lit, dungeonesque room. They finally get signal, from what they proclaim to be a new coffee shop who has not yet password-protected their network.

This scene, in its entirety, is a flawless introduction to the world of Parasite. The first, clear layer that is being peeled back here is the economic conditions of our protagonists, the Kim family. They live in a semi-basement apartment in the crowded metropolis of Seoul, filled with signs and symbols of their struggle to pursue an upward climb. The toilet itself, positioned in an almost throne-like manner in the slightly dilapidated bathroom, is the perfect metaphor for the position of the Kim family. In nearly every situation, a home toilet is positioned on the floor, as low as possible, so that waste can flow down into a septic tank usually located below the building. For the Kim family, however, the tank is high enough that the toilet needs to be positioned on a pseudo-altar - even the waste tank is above our protagonists.

The camera itself even tells this story - the film opens with an incredibly simple, but metaphorical motion. This downward pan reveals all that we need to know about the film’s narrative - below the street, below the sunlight, below the fan blade-pinned socks, lives the Kim family. They are the very bottom of this world, both physically and metaphorically. Bong is a master of these shots, creating visual metaphor that is so fundamental in nature, but filled with an unimaginable level of depth.

What follows is a wonderfully fun first act, penned perfectly by Bong. For those that have seen the film, the “surprise” of the act’s narrative is just as amusing, every single time. It is revealed that one of the many ways the Kims make a living is by folding pizza boxes for a local company, but they are quickly approached by the manager of said pizzeria with concerns about their accuracy and mistakes in folding. Ki-woo, played by Choi Woo-shik, is the youngest member of the family but is clearly shown to be the one with the widest aspirations of upward mobility. He stops his parents from fighting with the small-time pizza boss, and later finds YouTube videos to improve their folding speed and technique. Eventually, an old friend of Ki-woo’s visits the Kims, bringing with him the possibility of fortune, as well as a gift - a viewing stone, supposed to bring luck and money. “How metaphorical…” This friend is on break from University, and is viewed as the ideal young man in Korean society. He is leaving the country to study abroad, and suggests that Ki-woo take over his part-time job - an English tutor for a wealthy socialite’s daughter.

We begin to see the conniving nature of the Kim family as they weasel their way into upper-crust society through Ki-woo’s new gig. It begins with fabricating a college degree to gain the trust of the rich Park family, and very quickly evolves into something much, much more complicated. Following the first lesson with Park Da-hye, the naive young daughter of the uber-wealthy Nathan Park, Ki-woo overhears that the Park family is also looking for an art therapist for their son. The seed is planted, and Ki-woo is quick to cultivate it - he suggests his “friend” Jessica, who in reality is his sister Ki-jung. Two in, two to go. The young siblings continue their work posing as fellow patricians, all while also finishing the plan of infiltrating the Park family wholly and thoroughly. They stage implied misconduct by the Park family driver, planting evidence to suggest the old man had been having sexual encounters in the family car. He is quickly fired and replaced, of course, by Kim Ki-taek, the father of Ki-woo and Ki-jung. The Park family housekeeper is also ousted after the family skillfully convinces their employers that the middle-aged woman has contracted tuberculosis and is going to spread the disease if action is not taken. She is, as expected, fired, and replaced by the Kim family mother, Chung-sook.

Scene 2: The Midpoint

Our fun and games are over, and the Kim family has fully entrenched themselves into the highest level of Korean society. While the Park family takes a short camping trip, leaving their home empty, our four conniving schemers revel in the fruits of their labor. We watch as they spoil themselves in luxury - expensive liquor flows and the family nearly falls asleep on the couch that is bigger than their own apartment. The peace is broken by what I think is the greatest act turn in any single film. This empty silence is stabbed by an echoing, haunting ring - the doorbell. This scene is so jarring, both visually and aurally, for both the Kim family and the viewer themselves. It wakes you from the seemingly consequence-less plan that the Kims have pulled off, putting the entire scheme into question.

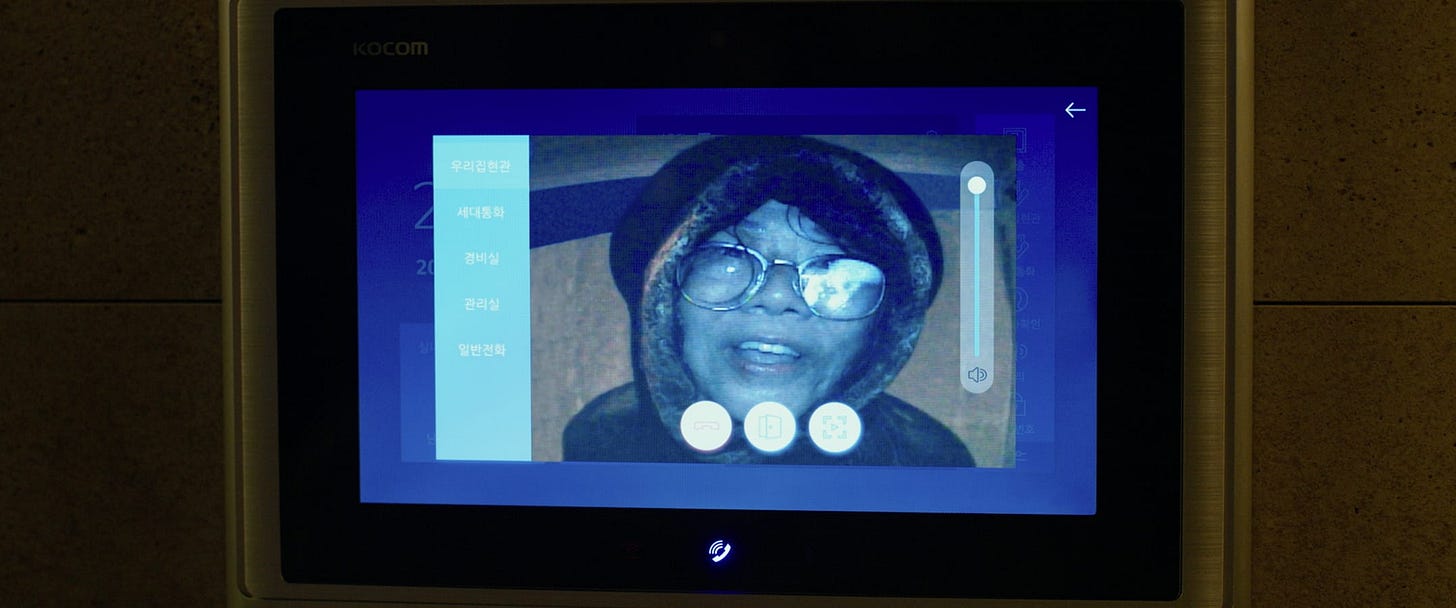

As the Kims stumble to sober up and address the situation, it is shown who is at the door - it is not the Park family returning from their rain-spoiled camping trip, nor is it a neighbor making a routine visit. It is, instead, Gook Moon-gwang, the former housekeeper who was fired for her forged tuberculosis. The way that Bong frames the entirety of this sequence is nothing short of genius - he utilizes the smart doorbell camera to give the first look at Moon-gwang in her new unemployment, presenting a remarkably haunting affectation via the fish-eye lens. Somehow, this seemingly innocent former housemaid has turned into a benevolent peace-ender, presenting the ultimate roadblock to a successful heist for the Kims.

With this simple doorbell, the floodgates (literally) open, and Parasite evolves into a pseudo-horror thriller. The tone of the film, in an instant, flips from a fun-filled, heist-like story about economic mobility, to a starkly eerie, tension-riddled suspense-fest. It is a remarkable way to put a folding midpoint into a screenplay - entering and leaving Parasite induce remarkably different emotions, and this single scene is the clearest inflection point. Moon-gwang informs her replacement, who she does not yet know is related to any of the other three house-servants, that she has “left something in the basement”. Chung-sook reluctantly lets her in, escaping the now torrential downpour outside, and leads her to the basement to retrieve her left-behind belongings.

Of course, those that have seen Parasite, know where this is heading. Moon-gwang left behind something that is quite important - her husband. It is revealed that her husband has been living in a rustic bomb shelter, hidden beyond a basement cabinet and winding concrete staircase, somehow surviving this semi-imprisonment for the entirety of Moon-gwang’s tenure. He can not leave the basement - eager loan sharks are waiting for his reappearance to exact revenge - but he can not stay either. With Moon-gwang’s dismissal, his subsistence has been halted. While she was previously making routine trips into the bunker to deliver leftover scraps of food and water, the new housekeeper clearly was not aware of his existence.

As skillfully as the Kims were able to execute their plan, they exhibit an equal level of clumsiness in dealing with this unforeseen complication. The remaining three family members, trying to observe what the Kim matriarch is dealing with in the basement, stumble down the cold staircase and reveal themselves to Moon-gwang and her bunker-bound husband. It is quickly realized that the four part-timers are not just independent totems in the Park household, but they are, in fact, related. The plan that seemed so successful continues to fall deeper and deeper into certain failure, capped off by an almost comical stick-up by the former housekeeper who now holds all of the cards. Moon-gwang and her husband threaten to reveal the Kims plot to the Park family, who have coincidentally announced their imminent return as their camping trip was rained out.

The Kims, against all odds, subdue the slightly-deranged couple, and manage to prepare for the return of the Parks. Chung-sook prepares a meal while the other three find hiding locations throughout the home. They banish Moon-gwang and her husband back to the bunker, and manage to hold out through a remarkably long night. While hidden under the enormous couch, the Kim family overhears the Park couple commenting on the smell of the home:

DONG-IK: "Hold on." (sniffs) "I know that smell."

YON-KYO: "What?"

DONG-IK: "This is Mr. Kim's smell."

YON-KYO: "Mr. Kim? Are you sure?" (sniffs) "I don't know what you're talking about."

...

DONG-IK: "I guess you don't know. I sit behind him every day so I know the smell."

YON-KYO: "Like poor people smell?"

DONG-IK: "No. It's not that strong. It's more like a subtle aroma that seeps into the air--"

YON-KYO: "Like old people smell?

DONG-IK: "No, no. How should I put it-- maybe the smell of an old radish pickle? Or that smell when you're washing a dirty rag?"

...

DONG-IK: "I mean I like his driving. And the man never crosses the line. Sometimes he teeters very close, but he never actually crosses it. That's all great. But that smell. It definitely crosses the line."This smell motif becomes incredibly important throughout the third act of the film, but for the purposes of this scene, it serves as the second turning point - the Kims have gone from vying for the respect of the Park family, trying very hard to win their affection and trust, to the exact opposite. The Kims now crave destruction - they will not be disrespected, and they will stop at nothing to ensure that they win this metaphorical battle.

Scene 3: The Long Night

The final scene that I think is important to highlight immediately follows the midpoint. In screenwriting, there is a concept known as “the long night” - typically, this is absolute rock bottom for the protagonists. When things seem like they can not possibly get worse, they drive one level deeper. In Parasite, the bunker fiasco seemed to be the lowest it could get. Our heroes were held hostage by a psychotic couple, threatened with losing their entire income source and their pride, and trapped to a couch-borne hail of invisible insults in regards to their physical being. The family manages to escape the Park household, only to be met with a biblical-level rainstorm that is flooding the entire city. Bong Joon-ho masterfully captures the literal descent back down the societal ladder, tracking the Kim family as they plunge from the wealthy hills overlooking the metropolis back to their sub-basement dwelling.

We watch Ki-taek, Ki-woo and Ki-jung desperately try to return home, ignoring cabs and awnings as they hurriedly trudge through the rain. The shots Bong fills this sequence with are unbelievably perfect - we see low-income apartments filling the dark night with yellow light, innumerable sprawls of shabby dwellings and a constant drone of sirens and yelling. As Bong himself writes in the screenplay - “the gates of poverty”. One shot, in particular, stands out from the rest: as the Kims continue their descent, we see them rushing down a gargantuan staircase from street-level to whatever lies below. Among the many other biblical references that Bong sprinkles into Parasite, this might be the starkest of all, as we witness a literal recreation of Dante’s Divine Comedy. As the rings of hell are reached one-by-one by our protagonists, their souls are punished, seemingly without refrain, in return for their crimes against society.

The long night concludes with, finally, actual rock bottom. Ki-woo wades through the now completely-flooded sub-basement, picking up family memorabilia and relics. Photos of Chung-sook and Ki-taek as a young couple, sentimental clothes and the entirety of the kitchen pantry are floating through the now destroyed apartment. At last, Ki-woo finds something worth saving - the viewing stone from the opening scene. Meant to bring luck and money, it has only seemingly brought misfortune. Ki-woo hoists the stone from the depths and hugs it - he continues to believe in the superstition. After all that has happened, only the stone can save the family.

The remainder of the third act of Parasite is something that needs to be seen to be understood. I can not reasonably explain the absolute chaos that unfolds following the flood, and there is no way to meaningfully summarize how masterfully Bong Joon-ho wraps up this screenplay. As I mentioned, this, to me, is perfect. Every scene relates to every other scene, in ways that are both clear and hidden. The story of economic mobility is winding, arduous and so evidently shown through basic camera motion. As the film ends, we get a reflection of the opening sequence: the camera pans up, through the sub-basement, as we see Ki-woo develop his next plan to save the family. The camera continues to move, climbing the street, as we cut to Ki-woo re-entering the Park mansion. Up, up, up, forever seemingly, as the film ends on a hill overlooking even the Park house itself.

Parasite is beautiful. It is undeniably well-written, visually stunning, and stuffed with an unimaginable amount of metaphor. I can not talk enough about what an achievement this film is, and just how perfect it comes across on the screen. The three scenes I have chosen to analyze are far from a complete representation, and the film only gets deeper with further re-watching. Bong Joon-ho is, truly, a master at work. From the introduction, to the jarring turn, through the long night and all the way into the melancholic conclusion, Parasite weaves a maze-like web of metaphor that can feel impossible to keep track of. Yet somehow, despite the labyrinth of layers delicately stacked by Bong, every single piece feels important. Every scene, every shot, every single line of dialogue is where it is meant to be. Parasite is perfection.