What is your idea of a romantic date? There might be candles, maybe music, but in almost every scenario, no matter the time or place, I am betting that food is involved. It could be filet at a steakhouse or deep-dish at a midwestern pizza joint, it might be oysters with wine on a boat or even just take-out on the couch. We eat when we are bored, we eat to entertain, and we eat in the moments both important and forgetful. Food is fundamentally romantic, it is just as much of a player in our game of life as we are, and there is no better depiction of cinema of this idea than Juzo Itami’s Tampopo. I want to shine a light on one of my very favorite classic films, and peel back just a few layers of this wonderful piece here. A sensual tour-de-force through Japanese culinary culture, centered on a rag-tag bunch of noodle enjoyers, this relatively understated film shows the timelessness of humor and smiles through a single, silent character - food.

Hors d’Oeuvres

Tampopo opens by introducing our heroes, two wayward truckers named Gorō and Gun. In their travels around the Japanese countryside, they routinely stop for an evening delight, a staple of national culture and cuisine - ramen. On the fateful night we first meet the pair, they stop at a run-down, decrepit joint known as Lai Lai, seemingly only occupied by gang members. Gorō rescues a young boy outside from ruthless bullying at the hand of three school children, learning that the boy is the son of the ramen shop’s owner, a middle-aged woman named Tampopo (dandelion, in English). After indulging in a less-than-stellar bowl of ramen, the experienced Gorō provokes one of the gangsters at the bar, a burly man named Pisken. The two fight, but our defiant trucker is overmatched, being knocked unconscious by the leather-clad thugs. Gorō and Gun stay the night at Tampopo’s home, waking up to yet another subpar meal for breakfast. While eating, she asks for their opinion of her ramen - “sincere, but lacking character”, Gorō tells her. On a whim, the truckers decide that this will be their quest, to help save her shop. This is the spark for our story, a journey that travels across time and space to solve an age-old puzzle: creating the perfect bowl of ramen.

If Tampopo’s ramen lacks character, director Juzo Itami is overflowing with it - as one of Japan’s most celebrated filmmakers, Itami’s work is regarded internationally for his technical ability, satirical screenwriting, and his ability to poke holes in a society dominated by tradition while maintaining light-heartedness. Tampopo is his magnum opus, the best example of his unique capabilities as a director. Technically, it is perfect - every shot is delicately constructed, with layers upon layers of foreground and background elements that can be watched a dozen times without boredom. The coloring throughout the film is gorgeous, painting Japan in the 1980s as a rose-tinted vignette centered around the key element of Tampopo, the humble bowl of ramen. As I will get into, there is an endless amount of cuisine shown in the film, and Itami showcases it perfectly. Each noodle, every fish cake, and individual chives all play their own roles in the film, creating emotion and intrigue in ways on par with the cast itself. This poetic wax about Itami’s perfection might seem stereotypical from a critical perception, but we have only scratched the surface here. Tampopo is more than just a story of redemption and growth, it is a roulette showing life in every color and hue. We will continue the story of Tampopo and her shop later, as Juzo Itami gives us more to stew on while we wait for the entree.

Soup or Salad

The premise of Tampopo is wonderfully funny and genuinely captivating, but what makes this film feel so much more alive than its simple underlayment is the wide array of side stories. Itami adds absurdity into the mix with a collection of minor anthologies, all depicting the keystone role that food plays in everyday life. We watch as a group of business executives sit down for dinner at a high-brow French restaurant, the epitome of wining and dining in the corporate panopticon. The first man, assumed to be the leader of the stodgy bunch, struggles with the urbane menu, settling on the simplest order he can find: Sole, a soup (no salad), and a glass of Heineken. The next man, facing similar troubles follows suit: Sole, a soup (no salad), and a beer (Heineken, of course). This game continues around the table as every single executive orders the exact same dish, a sign of both continuity and inexperience. Finally, the waiter reaches the last diner, a young subordinate and asks for his order: boudin-style quenelles (“As I recall, Taillevent in Paris serves them that way”), caviar sauce, an escargot pastry in fond de veau sauce, and the apple-and-walnut salad. And of course, Corton Charlemagne to drink (“Do you have a 1981?”). The staid elders have been upstaged by their lowly intern, losing at the universal game of culinary awareness.

In the same restaurant, we peer in on a women’s etiquette class teaching young girls how to properly eat spaghetti, insisting on the idea that no sound should be heard - the European way, of course. As she demonstrates, the camera pans to a white, presumably European tourist in the restaurant, slurping his heart away on a bowl of noodles. The women of the class all nervously eye their instructor before diving in, letting the noisy slurps convey their enjoyment for the meal. Later, an old man struggles as a dentist extracts a rotten tooth from his mouth. His recovery allows him to enjoy a soothing ice cream cone, with which he taunts a young child. The child’s mother has forbade sweets, and the young girl watches in agony as her dreams are devoured. An elderly woman sneaks around a supermarket, squeezing every single packaged item she can find as she is chased in a game of cat-and-mouse by the store clerk. The food stories get even darker as the film progresses, as we witness a con man using an expensive meal to lure a victim into an investment scam, wining and dining the man into submission. Ironically, the victim himself is a thief, lasered in on taking the con man’s wallet - only, he is so hypnotized by the meal that he forgets. Finally, a housewife on her deathbed makes one last valiant move before succumbing to illness, cooking a meal for her family, who mournfully yet thoroughly consume the dinner.

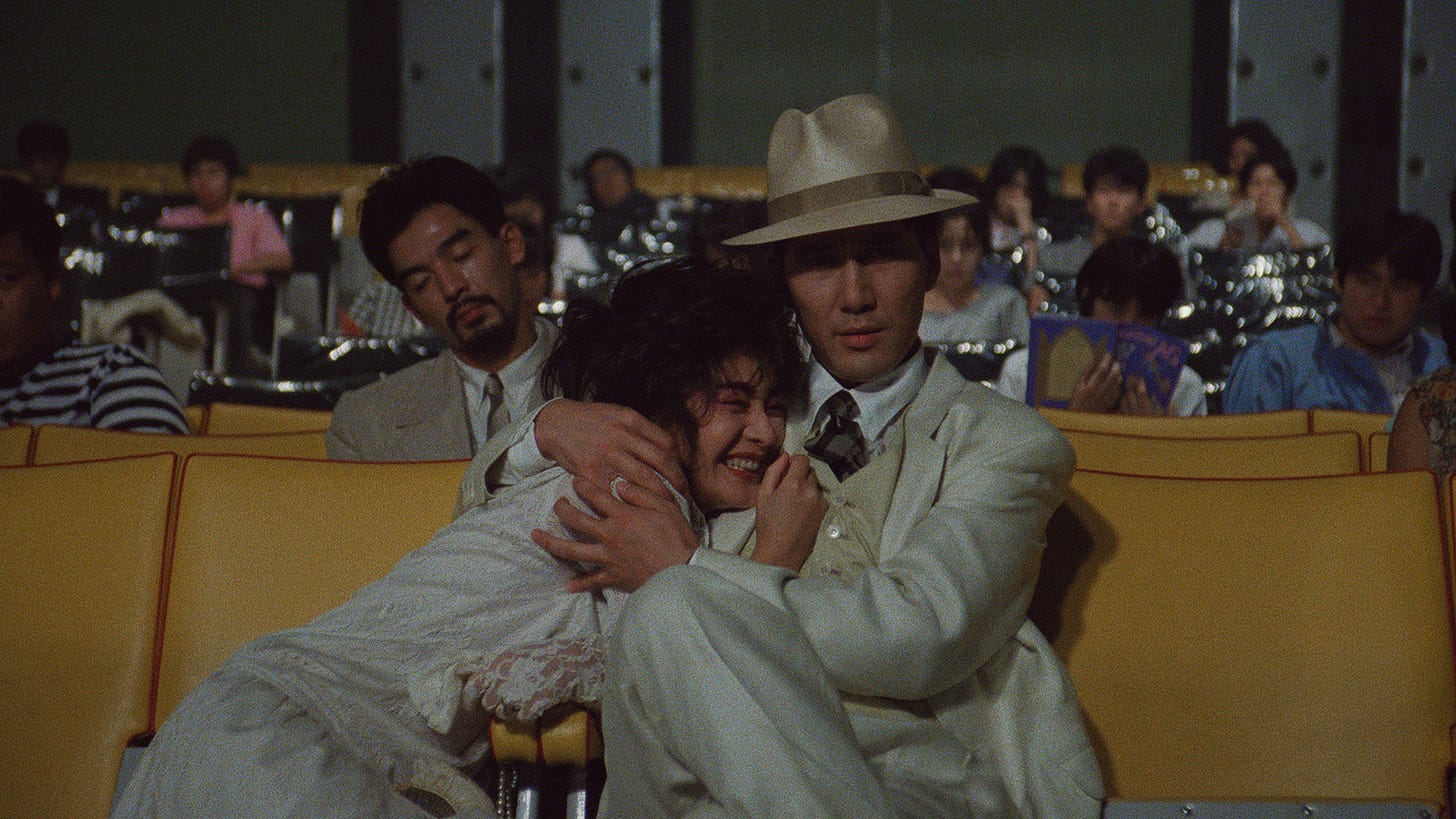

The film opens with the introduction of a man in a spotlessly white suit (played by Kōji Yakusho of Perfect Days) sitting down for a movie with his date, seemingly talking into the camera at us directly. The couple orders an elaborate theater snack, a whole chicken with all the sides imaginable. Throughout the film we revisit this couple, routinely watching them find new sensual ways to use food - oil, butter, eggs and whipped cream paint sizzlingly steamy pictures every time they appear. In the end, the man is shot in the chest by an unseen assassin, horrifying his lover. For the man in the white suit, however, this is satisfaction - at last, his life will end and he can watch as it all plays out like a film.

Now, this is a LOT of narratively unimportant screentime dedicated to these anthologies. The purpose feels nebulous and almost pretentious on the surface, but digging just an inch deeper reveals the true genius of Juzo Itami. In these short sequences, we see nearly every part of modern life: work and the odd culture associated with it, along with learning how to grow up and the unique mastering of manners required in Japan. The doctor and dentist, dating life, a weekend out and the weekly sojourn to the grocery store signifying the start of a new week. Outsmarting foes, being outsmarted, and finally, giving our all for our family. This is life, and in every single aspect food is present. It is no revolutionary idea to say that food is crucial for life, but the culture, the rules around food, these are what really guide the invisible hand of society. Life itself starts thinking about food, as the closing scene of Tampopo shows us a newborn baby breastfeeding on a park bench. Every character gets through this film using food as a central cog, and without the constant culinary movement we are left with a directionless simulation that can be described as nothing less than alien. Tampopo truly romanticizes and cherishes food in a way that no other film does, and it does it in the details, in the margins, in the small moments between. The food at our wedding, the school lunches, the steakhouse to celebrate a promotion and fortune cookies to fill a lone-wolf holiday, this is the beauty of life, the beauty of food, and the beauty of Tampopo.

The Main Course

And now, back to the meat of the screenplay, the story of Tampopo herself. Gorō and Gun agree to turn the ramen bar into the “paragon of the art of noodle soup making” - quite a high standard! The trio go to scout competition, to find what makes good ramen so good, examining every component along the way. As expected of a well-traveled trucker, Gorō of course has connections, the first of which is a homeless encampment populated by a series of impoverished foodies. The “old master”, a hunched over elder, is recruited to help Tampopo with her broth. Later, the group rescues a wealthy man from choking on his lunch, for which they are rewarded the services of the man’s chauffeur Shohei - of course, Shohei happens to be a master of noodle-making. Even the restaurant itself gets a refresh, as Pisken rejects his gang background to return to his true passion - interior design. Lai Lai is renamed to a catchier and more modern title for the ramen bar, taking on the owner’s personality as well as her name, now adorning the word “Tampopo” in large letters above the door.

This team, the Ramen Avengers if you will, are undoubtedly the highlight of the film. There is internal conflict, struggle after struggle, and finally triumph as Tampopo creates the perfect bowl of noodles. It is remarkably cheesy, that goes without saying, but that is the point. The film itself markets itself as the first “noodle western”, a play on the spaghetti western title given to so many American films of the 20th century. Every detail of tone plays into this - the music, the outfits, and the narrative all fit into this perfectly balanced dichotomy of surrealism and emotion. We genuinely root for Tampopo and her team as they work at an effort so seemingly miniscule, yet so endearing. She pays back loans, she gains confidence, and maybe most importantly, she improves the life of her son, as he has gained the strength and ability to fight back against his bullies. Tampopo is a simple story, a classic hero’s journey through failure and success, but somehow Itami turns it into so, so much more. There is never a moment without laughs or tears, without anxiety and anticipation, all for the simple bowl of ramen. It feels almost impossible to wipe the smile from your face as you witness Tampopo spy on her competitors to steal the chicken broth recipe or practice carrying pots full of water in a restaurant time trial, as every single scene gives the film its unique character. Tampopo is cheesy, it is endlessly hilarious, and it is overwhelmingly heartwarming, a true story of humanity in every single way.

Cherry on Top

For me, what makes Tampopo so much more than the sum of its parts (which are all excellent in isolation) is the wonderful taste that is imbued into every frame. The coloring, the continuous thread of themes, and the real hope that persists throughout Tampopo’s story is just unlike any other film. For a narrative so simple, Juzo Itami created an all-time classic of endless rewatchability, where every scene and line is cherished. The same care that Tampopo puts into her broth and noodles is given to the camera and script for the film, and the garnishes of chives and fish cakes are replicated in turn with Itami’s masterful ability to write satire. Japan is a culinary culture of both history and modernity, and the unspoken rules that are both respected and rejected characterize an ever-changing society. In Tampopo, we see that change happening in real time - our characters learn, grow and change through their food, refining their direction in life through the perfection of ramen. Intertwined with it all is the unique human sensuality, tastefully sprinkled in to give just enough uncomfortability to make the film work.

Tampopo is nothing if not a celebration of life itself, and of the food at the very center of it. The big moments and the small ones, the routine and the spontaneous, all are based on the desire to keep eating. Famed critic Roger Ebert praised the film’s ability to show “life as a series of smiles”, and I think there is no better sentence to describe Tampopo’s outlook. Whether it is meeting an old friend for drinks or enjoying a sandwich from a local deli, it could be an elaborate cake for a wedding or just one of your grandmother’s cookies, food is what defines our memory. The taste, smell and feel of life is captured in physical form, and remembered so often in fondness. Juzo Itami captures this so perfectly in Tampopo, depicting the never-ending change of humanity in such a beautifully simple metaphor, the humble bowl of ramen. In a meal so cheap and so ubiquitous, there is endless variation: bouncy or firm noodles, hot or savory broths, pork, chicken, beef and more, all topped with an endless roulette of garnish. Tampopo’s conclusion gives us the biggest joy of all, owing life’s greatest satisfactions once again to the culinary pursuit. As our group of ramen connoisseurs sample Tampopo’s final attempt at recipe perfection, silence cloaks the always-loud bar. The men, a five-way kaleidoscope of boisterous personality, have suddenly gone without voice and face, as they lift their bowls high in the air. Each man slurps the last drops of broth, becoming unrecognizable outside of a smooth porcelain mask - at once, life has meaning. Through argument and compromise, through trial, error, and triumph, our heroes have finally created the missing piece, the only thing that can truly connect us all - great food.